The dinosaurs became extinct because they didn’t have a space program.

~ Larry Niven

In Part 1, I contrasted some of the recent responsible analysis regarding the limitations of exclusively renewables thinking in energy transitions with a Bloomberg article that declared nuclear energy must be excluded on the basis of cost.

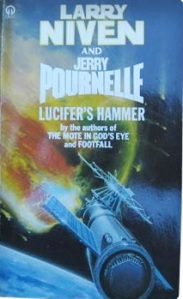

The atrocious arithmetic on which the author relied to perpetuate the solar, not nuclear story from a cost perspective was a fundamental, quantifiable error… But I’d like to devote Part 2 to a more personal issue I have with the article: the erroneous references to Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle’s 1977 novel Lucifer’s Hammer.

To most people it’s probably a casually-noticed pulp novel on the shelf beside Julian May’s Saga of the Pliocene Exiles. Maybe they tried to read it once or twice. To hard SF fans, and Larry Niven fans (like me) in particular, it’s the yard stick by which such films as Armageddon and Deep Impact came up so short – a sprawling, character-driven and scientifically thorough story of the before, during and after of a comet impacting the Earth. I re-read it a year or so back, so the mention by the Bloomberg author was immediately jarring.

To most people it’s probably a casually-noticed pulp novel on the shelf beside Julian May’s Saga of the Pliocene Exiles. Maybe they tried to read it once or twice. To hard SF fans, and Larry Niven fans (like me) in particular, it’s the yard stick by which such films as Armageddon and Deep Impact came up so short – a sprawling, character-driven and scientifically thorough story of the before, during and after of a comet impacting the Earth. I re-read it a year or so back, so the mention by the Bloomberg author was immediately jarring.

I devoured science-fiction novels like “Lucifer’s Hammer,” where a plucky nuclear entrepreneur restarts civilization after a comet almost wipes us out.

and

The plucky young entrepreneur raising enough money to build his own nuclear plant in “Lucifer’s Hammer” was pure fantasy…

Now, typical of Niven/Pournelle efforts of the time the novel has a plethora of characters, but the discoverer of the comet in the story, the titular hammer, is a wealthy man named Tim Hamner, owner of a successful soap company. His life of leisure is largely devoted to amateur astronomy; this includes operating a private observatory high in the Californian mountains.

This is as close as the novel gets to what the Bloomberg author has misremembered.

The nuclear plant that features heavily only towards the end of the book, after being introduced near the beginning, is the San Joaquin project. It was an actual 4 unit plant planned for California but halted by organised environmentalist pressure.

The story makes a point of its chief engineer, Barry Price, being a dedicated proponent and communicator as he sacrifices and works tirelessly to get the plant built and running. No entrepreneurship involved, but perhaps this was part of the Bloomberg author’s obvious confusion. Tim Hamner himself certainly appreciates nuclear energy, but at one point mistakes the cooling tower steam for polluting smoke, an illustration of a common error by the inattentive.

So, the comet gets closer and closer, then large pieces of it hit on both land and ocean, an epic event that spans several chapters and multiple points of view. The actual process of coastal inundation and abrupt nuclear winter are described in detail as our main characters all struggle to survive in various ways. Through fortunate geography and the presence and foresight of a respected senator, a rural community rapidly organises itself and its defenses against desperate refugees from below and encroaching snow from above, becoming known as the Stronghold. This is the remnant of civilisation which the surviving main characters aim for. Apart from Tim Hamner and his love interest, and the resourceful but flawed Harvey Randall and his friends, it’s the destination of the diabetic astrophysicist Dan Forrester from the Jet Propulsion Labs which tracked the comet.

It’s also the chosen safe haven of the astronauts and cosmonauts who were conducting research as the comet passed/hit. Niven and Pournelle’s narrative makes it abundantly clear that space exploration is their true cause – the nuclear plant is ultimately framed as just a potent resource with which the remnants of civilisation can rebuild such technological capacity far more swiftly.

To leave their readers in no doubt about how the authors regard the alternative in such desperate times, the antagonists are nothing less than a horde of cannibals led by an insane preacher, an army deserter and an anti-industry ex-politician. While lacking in all subtlety, it’s internally convincing given the death and rotting of all plant life after weeks of ceaseless rain, combined with the rapid depletion of all remaining accessible foodstuffs.

To leave their readers in no doubt about how the authors regard the alternative in such desperate times, the antagonists are nothing less than a horde of cannibals led by an insane preacher, an army deserter and an anti-industry ex-politician. While lacking in all subtlety, it’s internally convincing given the death and rotting of all plant life after weeks of ceaseless rain, combined with the rapid depletion of all remaining accessible foodstuffs.

The moral message at the book’s core is hinted several times but only pronounced plainly after the Stronghold successfully defends itself against an all-out attack by the main force of desperate cannibals, using crude explosives and mustard gas chemically synthesised under the direction of Dan Forrester (in the time he otherwise would have used to isolate the insulin he needed to live): civilisation has the ethics it can afford. This observation affects more than the cannibal prisoners-of-war (keep them as slaves? Execute them and save what they’d eat of the Stronghold’s supplies?), because if civilisation can afford higher ethics, it can accept more refugees and help more of the desperate, it can embrace greater gender participation, and expect better for the generations that follow.

So. We’ll live. Through this winter, and the next one, and the one after that… As peasants! We had a ceremony here today. An award, to the kid who caught the most rats this week. And we can look forward to that for the rest of our lives. To our kids growing up as rat catchers and swineherds. Honorable work. Needed work. Nobody puts it down. But… don’t we want to hope for something better? …And we’re going to keep slaves. Not because we want to. Because we need them. And we used to control the lightning!

~ Colonel Rick Delanty, Astronaut

This comes down to a final choice to make do with what the Stronghold has: relative safety, sufficient manpower, a good chance for many to survive the imminent winter… versus a last-ditch effort to defend the fragile power plant and its century-worth of abundant electricity from the remnant cannibals, who naturally see it as the epitome of unnatural, techno-industrial human hubris. Indeed, even the cannibal leaders share a scene where one briefly suggests sparing it – but not quite recognising that it would be the very means of delivering them from their desperate situation of dietary tyranny, if only their fervent ideological mindset could be shifted toward rationality.

Niven and Pournelle were futurists. Their forthright pro-technology, pro-industry, pro-nuclear narrative won’t be appreciated by everyone. Their characters spend a lot of time drinking, and many of the displayed attitudes are certainly of a past era. But they strived for technical accuracy: the San Joaquin nuclear plant was built by a major Californian utility – as a direct alternative to coal – not some rich idealist. When an author wants to offer a serious contribution, accuracy goes a long way.

The fiction narrative I think is eerily prescient is in Swift’s ‘Gulliver’s Travels’ (1726) when a character tries to store sunbeams in cucumbers to use them in the dark of winter. Sounds a bit like battery banks.

I notice that Australia has 3X the amount of gas fired generation compared to combined wind and solar. For California the ratio is 5 to 1. Too bad if US gas prices revert to what they were a decade ago.